March 14, 1994

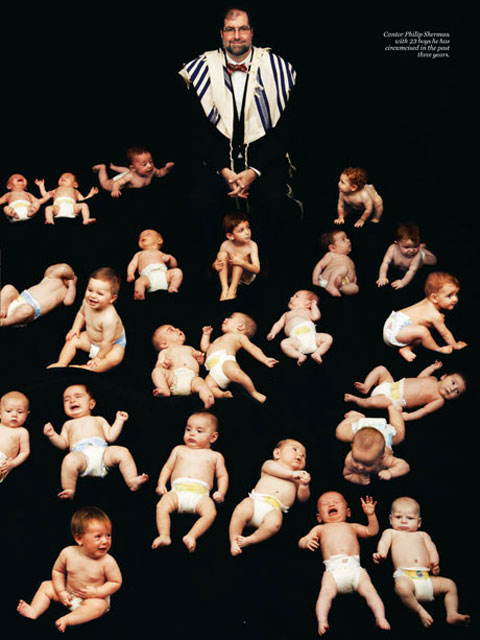

Mobile phone in hand, Philip Sherman, the mohel to Manhattan's power babies,

performs nearly 400 circumcisions a year.

Beeper-Friendly Mohel to the Stars

On a winter morning on the Upper West Side, Philip Sherman warned the crowd, "The baby is already crying long before I do anything to him. He will cry when his diaper comes off, and when he is held. After the bris, Marla (the mother) will feed the baby. Avrom (the father) will feed the guests." Cantor Sherman, 37, mohel to Manhattan's power babies, wore a dark gray suit and red-and-blue bow tie.

He had already put on his glasses, and now stretched his hands into surgical gloves. "Those of you who are within viewing distance and do not wish to be, now is your chance to find a new place to stand."

Philip Sherman is Manhattan's leading mohel (pronounced moyle: literally, "ritual circumciser"), with 16 years of experience and 3,500 surgeries under his and others' belts. Since 1990, when he gave up a position as cantor at the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue on Central Park West, Mr. Sherman has been plying the mohel trade full-time, and today he performs nearly 400 operations a year. In addition to being one of the busiest mohels around, he also boasts that he is the most expensive in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. His fee is nearly double the competition's, although, he added, he accepts whatever he is paid. He also performs baby namings for girls - no scalpel involved.

Philip Sherman is Manhattan's leading mohel (pronounced moyle: literally, "ritual circumciser"), with 16 years of experience and 3,500 surgeries under his and others' belts. Since 1990, when he gave up a position as cantor at the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue on Central Park West, Mr. Sherman has been plying the mohel trade full-time, and today he performs nearly 400 operations a year. In addition to being one of the busiest mohels around, he also boasts that he is the most expensive in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. His fee is nearly double the competition's, although, he added, he accepts whatever he is paid. He also performs baby namings for girls - no scalpel involved.

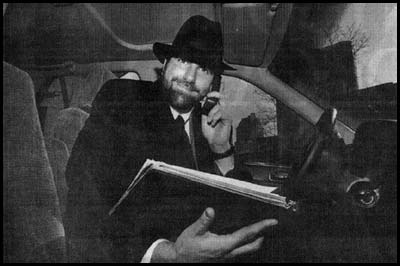

In an era when one can dial an 800-number to book a bris, Mr. Sherman schedules ceremonies by cellular phone, while he is racing from ceremony to ceremony in his red Honda Accord, later confirming via fax. His beeper number is printed in gold on the linings of the baby-blue yarmulkes he distributes at services.

"It's mohel marketing," he said frankly, in his Upper West Side apartment. "Eighty percent of my brises are in Manhattan. But I want to start branching out, getting into other areas." Last fall, he flew to Japan, performing circumcisions in Osaka, Tokyo, Yokohama and Sapporo.

"Bris" is the Hebrew word for "covenant" and the 3,500 year old ceremony, held on the eighth day of life, reaffirms the pledge between God and Abraham. At the West Side celebration - this one for the son of a Mt. Sinai medical School professor - Cantor Sherman cautioned the baby's grandfather to keep the newborn's legs pinned. "He'll try to get away," he said, "Don't let him. He'll surprise you; he's strong. Be stronger." As the mohel probed, the grandfather looked away queasily into a room of wincing males. The women had already fled to the foyer. "I know, sweetness, I know," Cantor Sherman cooed. "It's so tough being Jewish." The task accomplished, he wrapped the foreskin in gauze, and hid the bundle in his pocket.

Afterward, the baby's father said, "Sometimes I think when you have a new car, you have to put a little scratch on it. But I feel a lot better now."

The baby was sucking earnestly on a bottle of sugar water, amid staccato shrieks. Cantor Sherman smiled. "As I leave, a tremendous wave of relief will sweep over you," he said. "I'm not offended." He showed the parents how to replace the bandages, and savvily left business cards in the apartment. A check in one pocket and foreskin in the other, the mohel took off for his next appointment. (After each bris, Cantor Sherman buries the foreskin collected in his pocket in sidewalk planters around the city.)

In New York, Mr. Sherman's clientele are the children and grandchildren of real estate, publishing, film and music industry executives. (Real estate czar Harry Macklowe, the bond dealer Jim Lebenthal and CNN moderator Bernard Kalb all have male descendants who have used Mr. Sherman's services. In the interest of full disclosure, this reporter has a nephew in that category as well.) During the Persian Gulf war, while Scud missiles blitzed Israel, one well-wisher at a Sherman bris was a United Nations attache from Iraq. In high-profile Jewish circles, Cantor Sherman is called the "mohel to the stars." Some people said, "He has New York sewn up."

An Orthodox Jew from Syracuse, Mr. Sherman apprenticed with the chief mohel of Jerusalem during a junior year in Israel in the mid-70s, while earning joint bachelor's degrees from the Jewish Theological Seminary and Columbia University. "It was a very practical consideration," he said. His grandfather had been a rabbi, cantor and mohel, and the younger Sherman hoped to do circumcisions on the side, to augment his income. "I followed the guy around, and observed several hundred brises," he said. "I participated in changing the bandages, seeing the babies before and after, learning the psychology of it, the technical aspects and laws, and then eventually I was told, "O.K., you're going to do the bris today."

"The first five years, I was nervous, I sweated. Did I do it right? Did I say the right things?" Six years ago, he circumcised the first of his own two sons. He said that when he comes across his first patients, now in their teens, he forewarns the parents. "We're dealing with very fragile psyches. Just tell them 'He was at your bris.' "

Modern-day mohels like to stress their expertise and finesse, and, with his confident bris-side manner, Cantor Sherman is no exception. "What I hear is I have the fastest hands in the East," he said. His clients even include occasional non-Jews. "What we do is significantly different, better, quicker, faster, and less traumatic for the baby than what doctors do," he argued.

Zachary's father, John, held a camcorder, making a videotape his son would never want to see. Cantor Sherman cautioned him to shut off the machine before the moment of incision, then implored a guest, who was momentarily blinding him, to quit taking flash photographs. Without distractions the operation was successful. "Ladies and gentlemen, you're all invited to the bar mitzvah in the year 2007!" Cantor Sherman announced with practiced aplomb, and the crowd broke into laughter and applause.

Zachary's mother, Deborah, emerged from the bedroom, inconsolable. The guests converged on the food. Cantor Sherman stood by the foyer. A man approached. "It was great!" he said. "I truly thought I'd lose my appetite, but instead..." He held up a plate piled with bagels, salads and smoked fish. The mohel smiled. Then, after distributing business cards, he ducked through the door, moving like clockwork to a bris in a duplex apartment a few blocks away.

By James Sturz